RNOH Rehabilitation Consultant Dr Sedki explores prosthetics then and now / Terence Birch 2020

In February 2020 at the RNOH Herbert Seddon Centre as part of the 'Grey Lady' project, Dr Julie Anderson, Reader in History at the University of Kent, explored the legacy of over 41,000 British servicemen who lost limbs, together with Dr. Imad Sedki, RNOH Consultant in Rehabilitation Medicine, who presented his perspective on contemporary prosthetics and rehabilitation.

Historian Julie Anderson and the legacy of WW1 / Terence Birch 2020

The unprecedented numbers of amputee ex servicemen in the First World War is a huge challenge for the UK and its Allies, and the provision of today's prosthetics and orthotics has evolved from the challenges of their rehabilitation. Nicola Lane writes:

"From 1968 to 1988 I was a patient at Roehampton Limb Fitting Centre, as it was then known. I have now discovered that it was initially established by another determined woman like Mary Wardell - Mrs Gwynne Holford, who after a visit to a military hospital in 1915 vowed "...I will work for one object, and that is to start a hospital whereby all those who had the misfortune to lose a limb in this terrible war, could be fitted with the most perfect artificial limbs human science could devise.”

The original 'Roehampton House' had been requisitioned in the First World War as a billet for soldiers, and then became Queen Mary's Hospital for the rehabilitation of wounded soldiers 'who had the misfortune to lose a limb'.

In the photograph below from the IWM archives, we see the workshops at Queen Mary's Hospital for the re-training and rehabilitation of amputee ex-servicemen, and possibly one of the ex-servicemen being trained in the fabrication of artificial limbs:

'Finishing touches.' / © IWM Q 33689

Watch this incredible footage from the archives of the Imperial War Museum, a film on the work of the Army rehabilitation centre at Roehampton in the autumn of 1917, titled Repairing War's Ravages. It is a silent film and mysteriously titled in Spanish, but it is stunning and important documentation of these men and the systems of re-training being devised to mitigate the devastation of the First World War.

Throughout the UK different charitable initiatives provide re-training and rehabilitation for the wounded ex servicemen. Historian Julie Anderson identified the example of 'The Chailey Heritage Craft School and Hospital for Crippled Children' in Sussex. In the First World War it became a Convalescent Home for wounded soldiers called the Princess Louise Military Orthopaedic Hospital:

"Servicemen who had lost limbs in the conflict were sent to Chailey Heritage Craft School, set up in 1903 to provide a home and education for children with disabilities, to learn from the youngsters how to overcome their injuries.

At the school, an ‘educative convalescence’ programme allowed soldiers and children to learn and play together through activities such as agriculture, toy making, painting, music and sports.

The youngsters even built their own wooden huts, which they moved into to allow their original building, a former workhouse, to be used as a hospital for the wounded soldiers."

Wounded soldiers and Chailey Heritage Craft School children play football / Courtesy East Sussex County Council Archives

A rare link between the First World War and the RNOH was provided by Jane Robinson, a Member of the Friends of St Paul's Cathedral, who has been researching the 'First World War Altar Frontal' given to St Paul's Cathedral in 1919. Jane shared this cutting:

Courtesy Jane Robinson

" Queen Alexandra …visited the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital in Great Portland Street and inspected a number of pieces of embroidery work which have been done by wounded soldiers under the tuition of Lady Mary Dormer, whose father, the Earl of Denbigh, is chairman of the hospital. On screens were many examples of embroidery...The Surgeons have expressed their sense of the value of the work in helping the men to regain the use of their hands and fingers. The Royal Orthopaedic Hospital was the first to be selected for the special treatment of soldiers with bad wounds of the arms and legs, and since early in 1915, three thousand cases have passed through..."

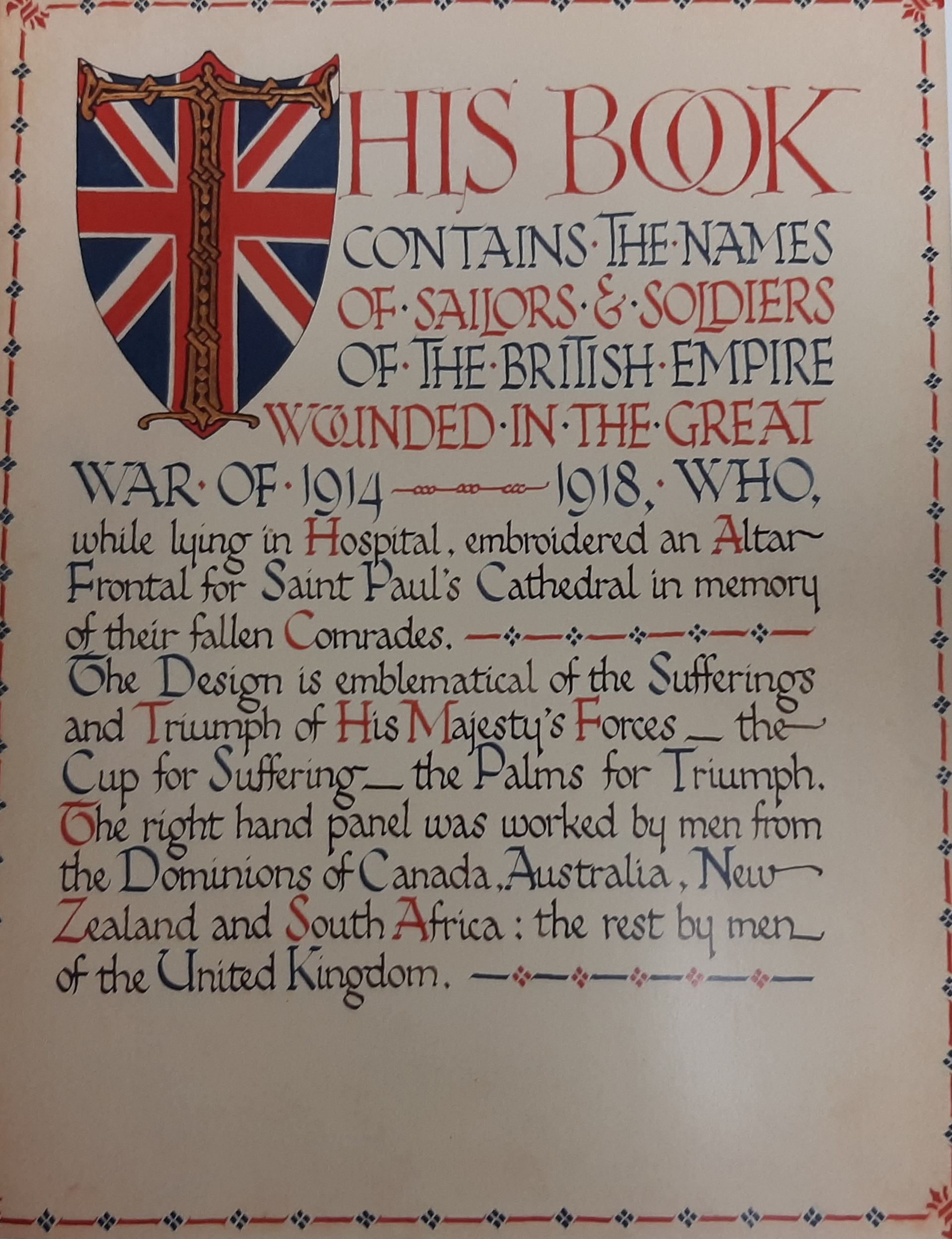

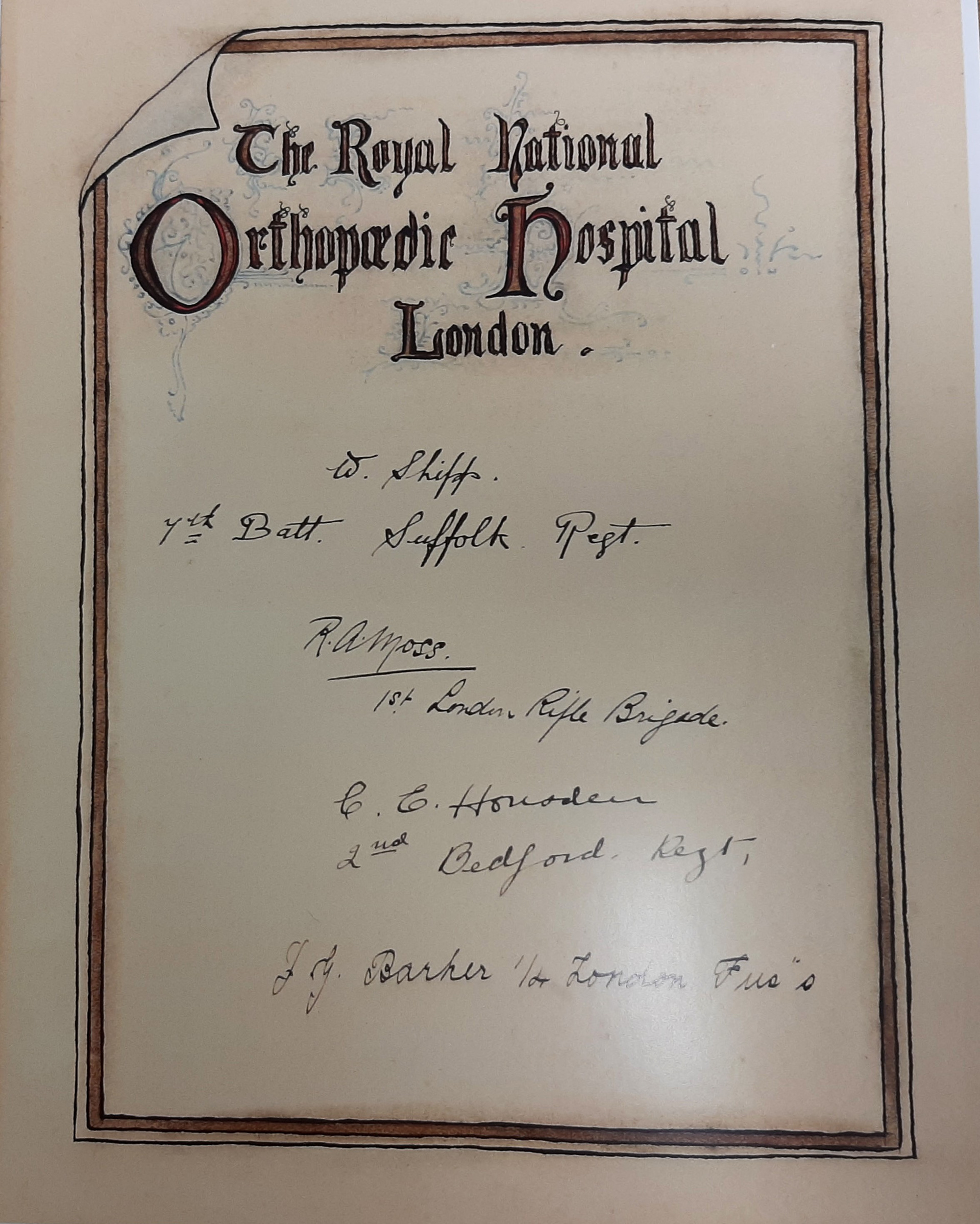

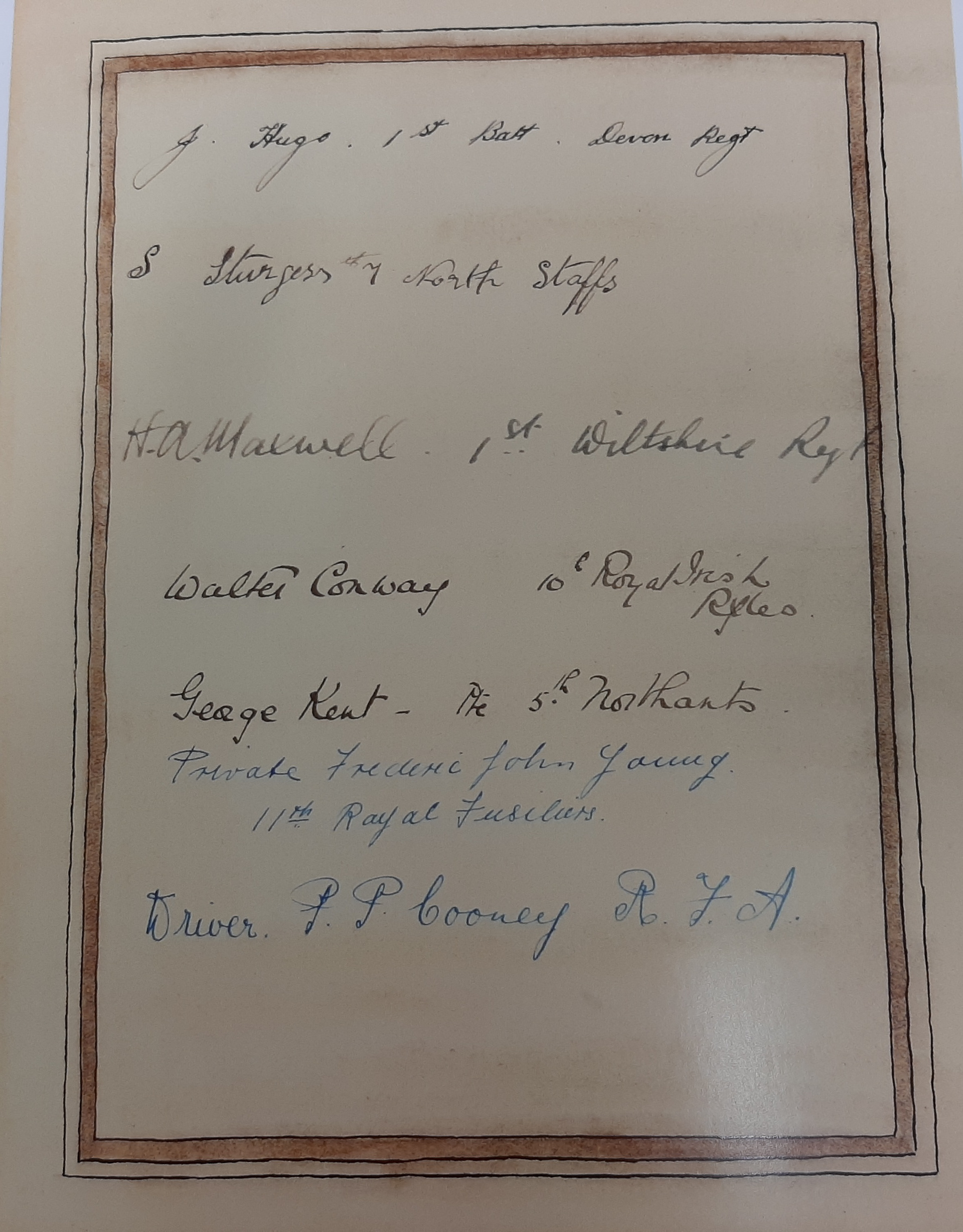

During Jane's researches she found no direct 'paper trail' of archives relating to the First World War at the RNOH. But she told Pegleg Productions about a Memorial Book that goes with the Altar Frontal, listing the names of the ex-servicemen cared for at the Great Portland Street RNOH who contributed embroidery for the panels.

" This Book contains the names of Sailors and Soldiers of the British Empire wounded in the Great War of 1914 - 1918, who, while lying in Hospital, embroidered an Altar-Frontal for St Paul's Cathedral in memory of their Fallen Comrades..."

St Paul's Cathedral First World War Altar Frontal / images Courtesy of Jane Robinson

Pegleg Productions is grateful to Jane Robinson for sharing this story, which also illustrates the frustrations of researching the First World War and its wounded soldiers - the absence of records, the narratives and people lost in time. The Altar Frontal was presumed to be destroyed in the Blitz, then re-discovered in storage.

The participating soldiers were from all over the Commonwealth. Check out this account, which includes the story of a Canadian soldier and his contribution:

As reported in the 'Journal of Design' Vol 31 Issue 1, the 'Disabled Soldiers Embroidery Industry' was a high profile scheme that lasted from 1915 to 1955:

"...Perhaps the most successful and high-profile scheme that aimed to help disabled combatants, returning from the First World War, back to employment through the small-scale production of domestic and luxury textiles marketed to middle class and aristocratic consumers. Its contribution to the modern revival of interest in embroidery is clear from its widespread promotion in newspapers and women’s magazines..."

In reference to the RNOH Surgeons' appreciation of the rehabilitation value of embroidery, pictured below is one of the found copy negatives, titled 'Rehabilitation Hand Exercises after Operative Treatment' - including the action of weaving, in the bottom row middle pane.

'Medical Photographic Department, Institute of Orthopaedics, Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital' / Courtesy RNOH / Nicola Lane 2019

In 1919 a Peace Parade marks the end of the First World War. But the wounded are largely unrepresented - many had been paid to stay at home.

Nicola Lane writes: "It could be argued that this erasure of the wounded represents an important aspect of the First World War, which is common to other conflicts and traumas: the desire to put the trauma away, and move on. Sometimes this desire can erase memories, history and people. What we remember and what we forget can be an unconscious decision, or a deliberate choice, or determined by others."

'Fragments from France and elsewhere meet the Future full of Faith and Hope' Roehampton 1916-1917 © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

*

For the next chapter in 'Our Search for the Grey Lady' go to: